Notes on the film

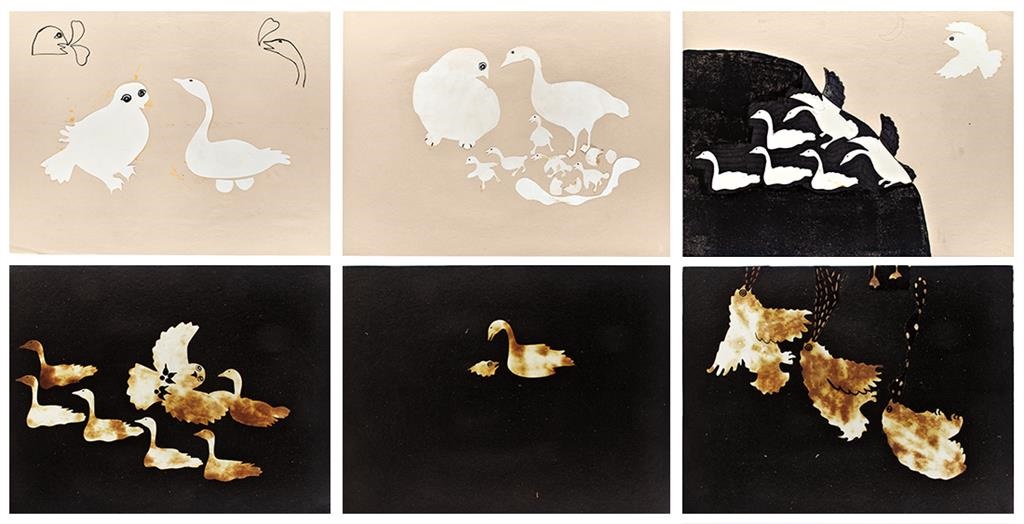

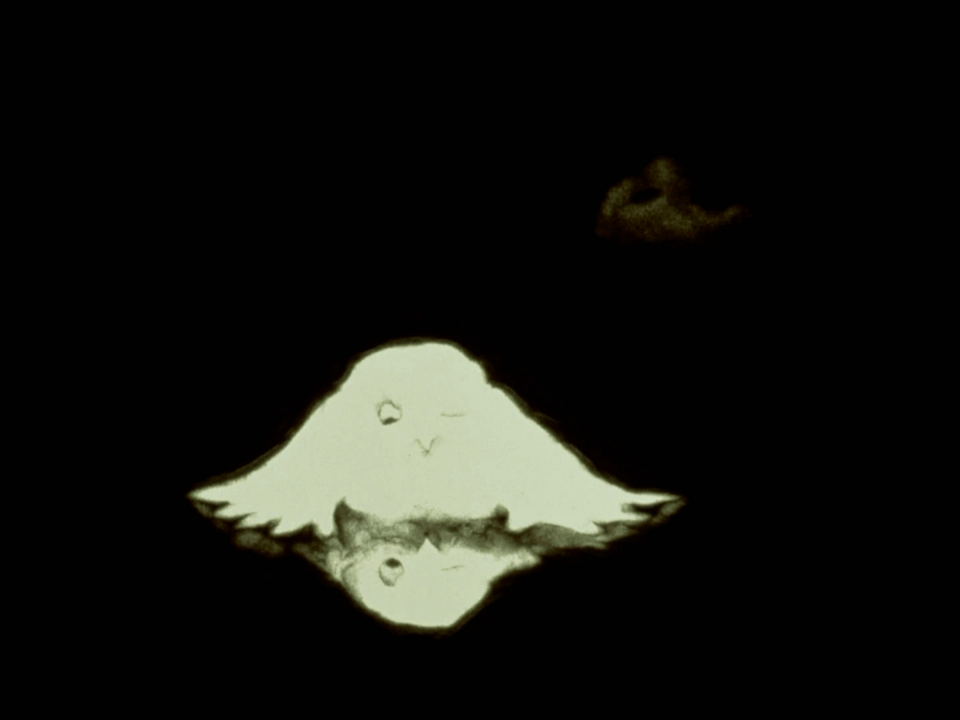

The Owl Who Married a Goose is a sand animation that adapts an Inuit legend about an owl who defies nature by marrying a goose, only to be humbled by his physical incompatibility. This film was produced by the National Film Board of Canada as a collaboration between animator Caroline Leaf and Inuk artist Agnes Nanogak – part of a series titled Eskimo Legends (an outdated term for Inuit people no longer used today). Working directly under the camera, animator Caroline Leaf sculpts each frame by hand using beach sand over a lightbox. The varying densities of sand allow for nuanced transparency, producing a rich range of tone. Leaf skillfully uses this effect to differentiate between fluid and rigid substances: tight dense clusters act as solid bodies, while fanning the grains into loose scatters suggests lightweight feathers or splashing water droplets. Layering denser forms atop lighter ones creates a strong sense of depth and dimension.

various techniques with sand create rich visual texture, while movement remains fluid and precisely controlled

Underlit sand animation centers the expressiveness of silhouetted forms and makes them central to its visual storytelling. This film’s visual style relies on striking designs by Inuk artist Agnes Nanogak, who created its distinct animal silhouettes. Women from Baffin Island also contributed to the soundscape by mimicking animal calls– a practice rooted in traditional hunting. In an interview about her creative process, Caroline Leaf expressed discomfort in personalising a story that belonged to Inuit oral tradition for generations. In adapting a traditional Inuit story for animation, she strived to take the position of an interpreter rather than a storyteller. The film’s Inuktitut dialogue was left untranslated in most released versions, preserving the story’s linguistic and cultural roots. At the same time, Leaf’s interpretation diverges from the traditional narrative, as she portrays the Owl with gentle empathy instead of intended ridicule.

silhouettes by Inuit artist Agnes Nanogak shaped the character design

Caroline Leaf’s distinctive animation style is most recognisable by her long unbroken shots with fluid metamorphic transitions. Leaf is adept at exploring the versatility of sand – shaped into delicate snowflakes and hard eggshells alike– simply by altering the spread of its grains. The textural diversity, perspective, and scaling further enable her to render rich environments using only monotone. The backlighting from the lightbox heightens this contrast of black against white, turning negative space into an expressive visual tool. Sand becomes the environment itself, taking on the disparate roles of sky, land, and water– speaking to the film’s main theme of two creatures from different realms.

From a production standpoint, Leaf’s process with sand animation is thorough and deeply focused. Animating straight ahead does not permit retakes, and Leaf expressed the pressure in needing to work with intense precision. At the same time, she embraced small errors, knowing they last only a few frames before being reshaped or replaced. To create movement, she carefully charts out the motion by redrawing the silhouette before erasing the previous drawing, giving her a perceptible sense of consistent volumes with each frame. Each frame is built by hand and a few other simple tools like a pipe cleaner, comb or a fork to carve details and textures inside the shapes.

along with her hands, Leaf uses different tools to add rich textures

Animation workshop by Caroline Leaf

A hands-on workshop where Caroline Leaf uses the lightbox to demonstrate the techniques and process behind some of her most iconic works, including The Owl Who Married a Goose.

Hand-Crafted Cinema Animation Workshop with Caroline Leaf – NFBStefen Tiefengraber’s live audio-visual performances

To see the audio-visual live performances that coincide with this work

Agnes Nanogak Goose | IAQ Profiles | Inuit Art FoundationAn analysis of Inuit Animation

Suzanne Buchan examines the NFB’s Eskimo Legends series alongside similar projects, providing insight into the social and political contexts that shape Inuit art and storytelling.

Read the chapter