Notes on the film

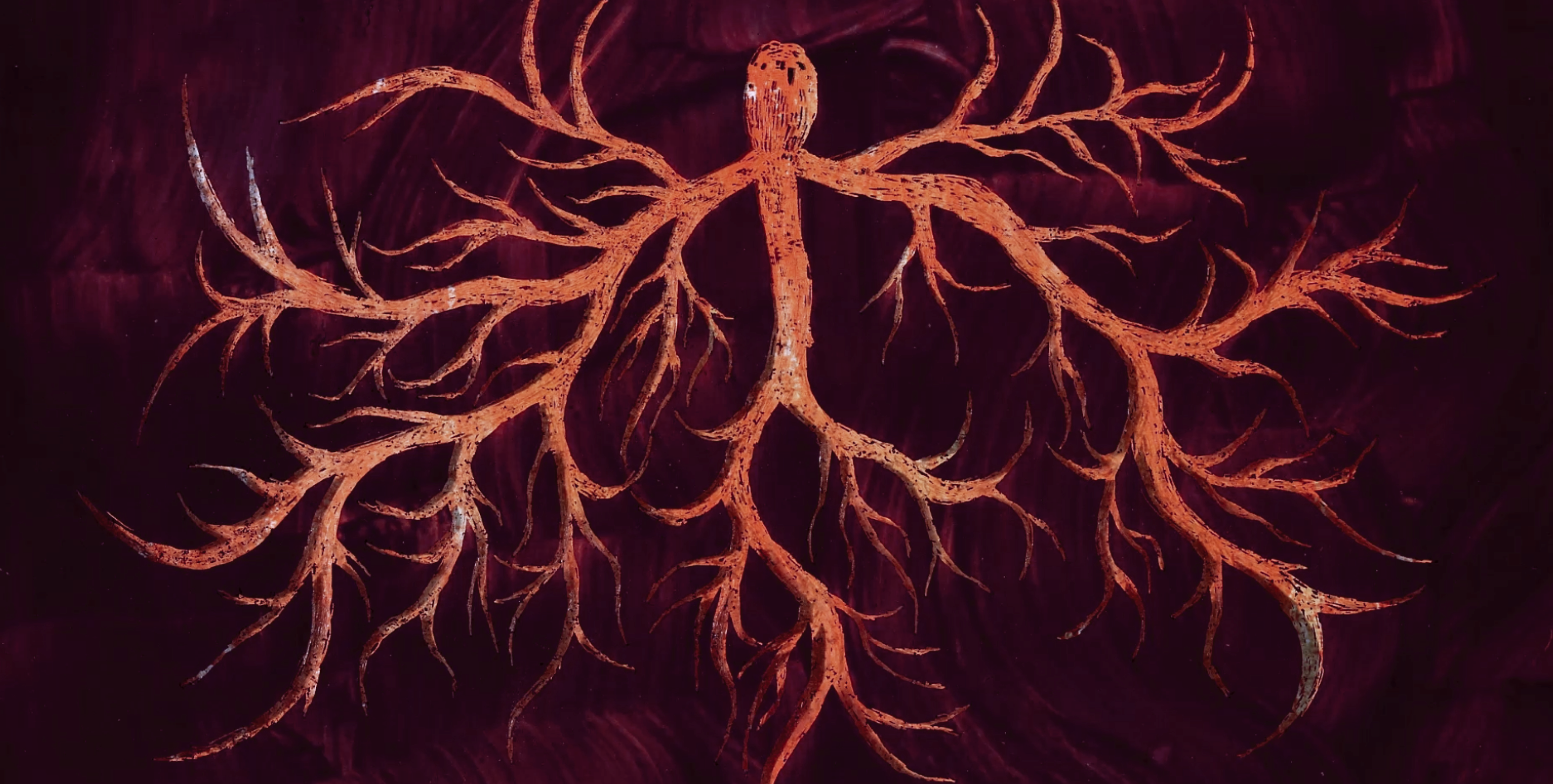

The Street is an adaptation of a short story by celebrated author Mordecai Richler, rendered in ink and watercolour on underlit glass. Animated straight-ahead under the camera, director Caroline Leaf crafts striking, dimensional frames in predominantly muted browns that evoke family photographs and the passage of time. The film explores the observations and experiences of a child growing up in Montreal’s Jewish community during his grandmother’s final days. The narration is guided by the voice of the adult protagonist, whose recollections of this childhood event are infused with nostalgia for his family and community. Caroline Leaf visually captures his layered recollections using loose, continually shifting hand-painted sequences. The film’s fluid scene transitions, achieved by moving and layering paint, mirror the way memories glide and overlap. Leaf’s technically impressive painted renderings of camera angles, parallax, and foreshortening also evoke the selective, elusive nature of memory and the shifting scale of a child’s view of the world.

Although the film’s plot pivots on familial grief, Leaf follows Richler’s story in capturing the playful, sometimes unintentionally naive ways children experience death – preoccupation with inheriting the empty bedroom and avoiding lingering ghosts – and slice-of-life routines of a bustling household. The film moves at a gentle pace: dinner table conversations, petty sibling fights, the steady rhythm of daily life. When death finally arrives, it does so abruptly, and Leaf visually scripts the emotion that follows. When the young protagonist enters a house filled with mourners after the grandmother’s death, the composition evokes a sense of disorienting claustrophobia using tight, congested framing, continual angle shifts, and overlapping voices.

fast camera movement, congested framing and tight spaces capture feeling overwhelmed

Leaf is an influential figure in under-the-camera animation, developing methods that achieve fluid, continually shifting visual cinematography. For this paint-on-glass film, she mixed glycerin into ink and watercolour to keep the medium workable for long periods, allowing her to manipulate it with fingers across the surface (much like sand in her other works). The scenes were painted on flashed opal or windowpane glass with just a few tools—a wooden stick to carve in details and a cloth to lift excess paint—relying primarily on touch. Some traces of shifted paint were deliberately left in the frame, preserving the evolving gestures of animation as part of the film’s texture and artisanal craft. Perhaps most distinctive is Leaf’s use of long, unbroken shots, born out of necessity. As she has said, “All my animating life, I did not know how to make an edited cut, I found my way around the problem by making morphed scene changes. Some would say my animation is noteworthy for its moving camera and morphing scene changes. I credit my originality to the animation class where we were left alone for the most part and found our own solutions.”

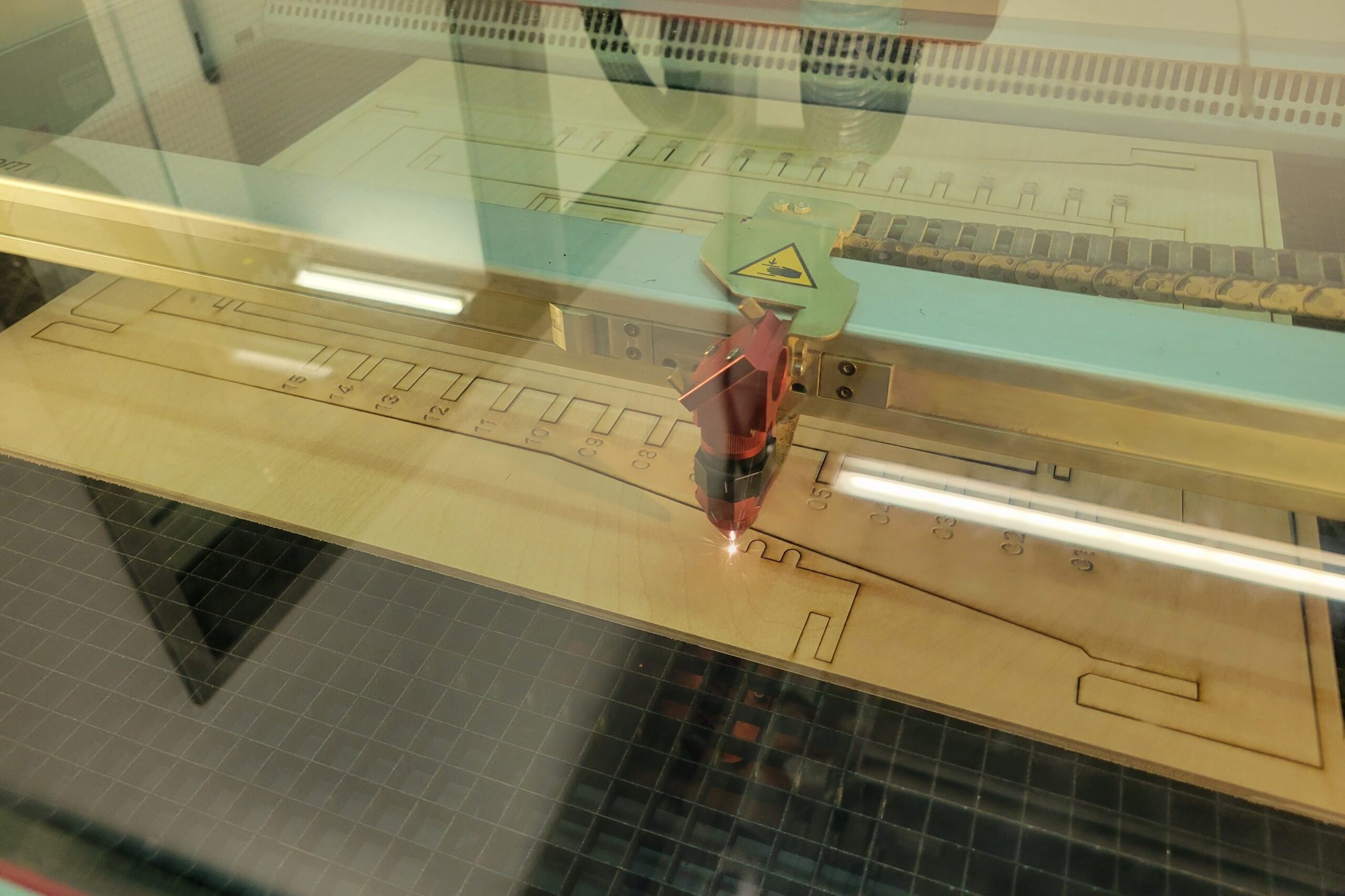

a behind-the-scenes still of Leaf using her fingers to move paint across a glass panel, meticulously crafting the film’s aesthetic

Interview with director Caroline Leaf

This audio archive is a retrospective conversation with Caroline Leaf, reflecting on seven of her films, her journey as an animator, and her unique approaches to technique and materiality.

The Animated Art of Caroline Leaf – Harvard Film ArchiveAnimation workshop by Caroline Leaf

A hands-on workshop where Caroline Leaf uses the lightbox to demonstrate the techniques and process behind some of her most iconic works, including The Owl Who Married a Goose.

Hand-Crafted Cinema Animation Workshop with Caroline Leaf – NFB